(This post was first published by The Dabbler in September 2011)

They were built in a 30 year goldrush, the old English football stadia, and when they were new, there’d been nothing like them in the world since Byzantium. Fifty years after London tooled-up in preparation for the great Chartist meeting on Kennington Common, England had at last lost her fear of large gatherings of her people in the heart of her towns and cities. The football stadia were the places where this happened, often accompanied by disorder but never enough to spook the authorities into rollback. For such novel structures, they proved longlasting, but now they are nearly all gone. One of the most extraordinary indeed – but I’ll come to that later on: I’m talking about Burnden Park, for 102 years the home of Football League founder members Bolton Wanderers F.C.

The great period of English football stadium building stretches between 1895 (Everton’s Goodison Park) and 1923 (Manchester City’s Maine Road and the climax to it all, Wembley). Burnden Park was one of the very first to go up, constructed on open land on the town’s south-east, but the relatively fresh air on the edge of the city didn’t last, and Burnden was quickly engulfed by new building. The stadium secured Bolton Wanderers’ future. Those clubs that didn’t get their stadium up by 1923 left it too late: today’s top clubs remain those who built in the goldrush.

On 27th April 1901, 22,000 people were at Burnden Park to see John Cameron’s Tottenham Hotspur overcome favourites Sheffield United in the replay of the FA Cup Final. Far more telling in the cultural sense, however, given the town and stadium’s modernity, was the 1904-05 visit of the film makers Mitchell and Kenyon. Football and early film went together so naturally – both brand new, both crazes, both crowd-pullers, and M&K filmed matches by the hundred. It’s almost impossible for the modern eye to see a Mitchell and Kenyon film as a thing of freshness and excitement: where’s the dirigible? where’s the Art Deco, the jazz and tall buildings? But that’s what their arrival in Edwardian Bolton was replete with all the same. It’s what film said in 1904/05.

In this one (Bolton v Burton United) ignore the game: keep your eye on that tall chimney. And watch the railing at the top left.

What we’ll never recreate from the childhood of our towns and cities is the smell of the air. The paradoxical message of smoke: it stings in the back of your throat, but something exciting is going on..

Bolton the football club had a good 1920s, winning the FA Cup on three occasions, including the Wembley White Horse Final of 1923 which saw the biggest attendance ever recorded at an English game. 123,000 were there officially, but the real figure was closer to 200,000: we will return to the overwhelming of football grounds in a moment. But the cultural high point of the stadium’s pre-War history came with the arrival in Bolton of Mass Observation’s Humphrey Spender in 1937.

Spender was a pioneer of British documentary photography and hated it: although he took over 900 photographs in Bolton in 1937 and 1938 with his 35mm Leica – an enviable piece of kit to this day – the intrusiveness of his work wore him down. A lot of his pictures show the insides of pubs. They were good places to listen and record, and he could take the edge off. But he also went to Burnden Park.

He proved luckier with the weather than Mitchell and Kenyon thirty years before him (Mitchell was still alive, working quietly a few miles away in Blackburn) and captured terraces occupied, it would seem, by Larkin’s fools in old style hats and coats… men more prosperous in appearance than you might expect in the circumstances. Was this Depression, driving poorer people out of the game, or just respectability?

Later on, Spender caught up with a slick young star being mobbed by his fans before boarding the motorcoach back to wherever.

You can see most of Spender’s Bolton here. No longer the rapidly-expanding new town of Mitchell and Kenyon, Bolton is said to have depressed Spender with its spartan nature. But to this modern eye the town looks settled, civilised and in control of itself. Monochrome does that: it cleans and dignifies. For all that, there was dignity here already: this was a town negotiating the Great Depression, and Spender’s images are appropriately respectful.

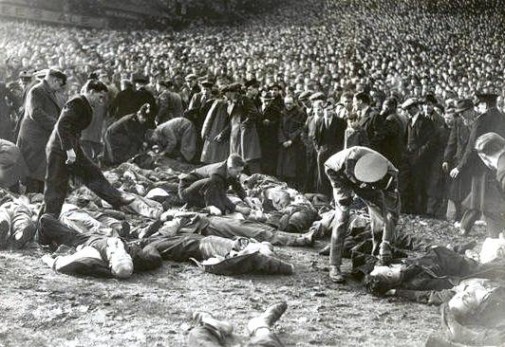

Burnden Park was supposed to be able to hold 70,000 spectators, but before the 1971 Ibrox Disaster capacity was an inexact science. The official record attendance occurred shortly before Humphrey Spender arrived: 69,912 for Manchester City in 1933. But more were there on 9th March 1946 to see Stanley Matthews play for Stoke in the FA Cup. 50,735 were counted, but some estimates put the actual number at about 85,000. It was a difficult day to superintend. One stand was still closed because of ongoing war requisition, and another’s turnstiles were out of action. 9,000 people had to enter elsewhere and walk around the pitch to their stand. Twenty minutes into the game, on the massive terraced stand beside the railway, railings holding up the crowd strained, and then broke.

In his autobiography, Stanley Matthews said

“As we trotted on to the pitch I noticed the crowd was tightly packed, but this was nothing unusual at a big cup-tie. Our boys began well, and after ten minutes we had reason to feel confident as we were having the best of the game. It then happened! There was a terrific roar from the crowd, and I glanced over my shoulder to see thousands of fans coming from the terracing behind the far goal on to the pitch.”

The surge and resultant crush killed 33 people, many war veterans amongst them.

Matthews wouldn’t win the FA Cup that year, and he’d be on the losing side in 1948. When his turn famously, finally came around in 1953, it coincided with what might be considered to be Burnden Park’s greatest, happiest moment. Such a contrast to the horrors of March 1946: 1953, Coronation Year, Everest Year, was also the year Burnden Park was painted by L.S. Lowry.

Painted by Lowry! The twentieth century had no greater British cultural honour that could be paid, and although the picture itself is an extraordinary, timeless pulling-together of the whole British urban industrial experience and adventure, it coincided with a great Bolton moment. Bolton’s Nat Lofthouse, the “Lion of Vienna”, was Player of the Year in 1953, and scored 30 goals in Division One. He took Bolton to the Cup Final that season, where they’d meet Matthews and Mortensen and the Queen.

There would be more – the railway stand would appear in John Schlesinger’s A Kind of Loving in 1962, the marvellous Alan Bates/Julie Christie rendition of Stan Barstow’s great novel. In the 1930s and 1940s, the Humphreys Spender and Jennings had turned the culture: ordinary working people were being represented not as jokes, problems, threats or aborigines but as full, rounded beings with dignity and intention. It’s possible that A Kind of Loving was one of the first steps on the road away from that, the road to Little Britain and Shameless. At any rate, after Lofthouse’s retirement, both Bolton Wanderers and Burnden Park went into decline. In 1986, one corner of the railway stand was torn down to make room for a supermarket. Bolton went down to the Third Division.

It would have been unjust, with all that had gone before, for the story to have ended so. It didn’t. Burnden Park’s last match was a joyous, sunlit promotion celebration in 1997 and victory over fellow back-from-the-dead club Charlton Athletic. The last season at Burnden Park saw 100 league goals, 98 points and the Division championship. Waiting in the near future was a bright new stadium, Sam Allardyce, Jayjay Ococha, Youri Djorkaeff and European football.

The railway behind the terrace has closed now, and another, bigger supermarket – Asda – stands on the Burnden Park site. They are reported to have hung enormous pictures of the ground and its great players high over their tills in memory. That’s appropriate for Burnden Park, pioneer itself and a landmark place in the lives of pioneers and painters and auteurs: a home to great tragedy and yet wholly undefined by it, remembered in happiness in distant corners of the world in a way given to few buildings and few forms of architecture.